The Last Pagans of Europe by Thomas Vitkus

Folks, thanks to Drulia, I’ve just learned something very interesting new but very old indeed! So I went to Medium.com and stole this from Thomas Vitkus! (Shhhhhhh Please keep quiet and don’t tell Tom about this!) The more I learn the more I realize I know so little, indeed!

The Last Pagans of Europe

Dec 15, 2019

The survival of the Lithuanian nation is perhaps one of the most epic yet least known tales of human history. The ancient language, religion, and customs of this unique and prideful culture has survived a thousand years of relentless bombardment thanks to one of the most unlikely sanctuaries: the home of the peasant. “Stubborn pagans,” to quote an 11th century Archbishop, is a description which would go on to accurately convey the Lithuanian character from the medieval crusades into the 21st century. Adamantly refusing to abandon the land and ways of their ancestors, Lithuanians continued to practice in the ways of their religion and ancestors even after their official conversion. King Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania in the 1300s, described his people as “iron wolves”- unified and standing tightly shoulder-to-shoulder like a pack.

Yet not many today know Lithuania even exists. It’s home to a mere 2.8 million people which makes its population slightly smaller than that of Kansas, and it’s only a third of the state’s size. The landscape is characterized by gentle farmland punctuated by hillocks, ancient oak groves, and islet-strewn lakes. The old pagans of Lithuania considered these lands sacred and believed all things had spirits and a right to be. Farmers would plow around boulders rather than remove them, and bees were so revered that most people practiced bičiulystė — selfless beekeeping for moral purposes, and not for financial gain. The most sacred place to the ancient Lithuanians was the mythic Romovė (row-mow-veh), which translates as “sanctuary.”

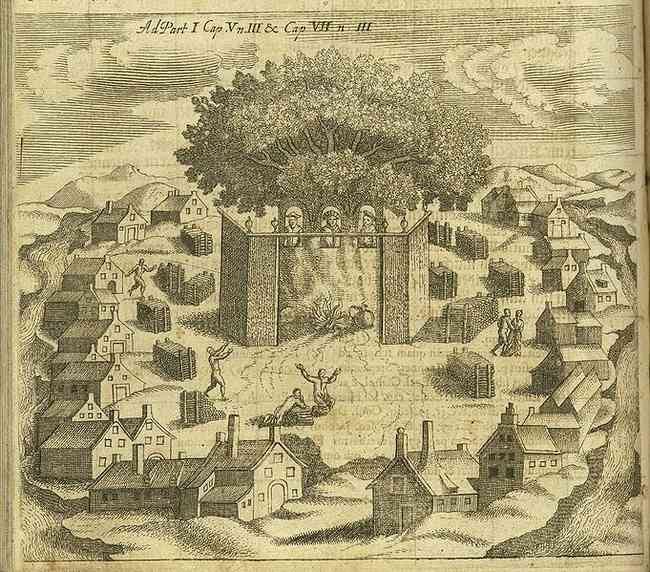

Romovė was said to be a colossal oak tree surrounded by a holy grove. At its foot was a flame altar called an aukurus which was kept burning day and night. It was believed that Gabija, goddess of fire, resided in this altar, and the oak tree itself housed statues of their most important deities. In 1009CE, the missionary Bruno of Quefurt was beheaded after trespassing into the holy grove to chop down trees and destroy idols. The report of his murder was the first time Lithuania was ever mentioned in the written record. It was followed by nearly four hundred years of crusade against the Baltic pagans, and nowhere in the world did the Teutonic hordes face such fierce resistance.

On the feast day of Saint Matthias in 1336 Lithuania, over six thousand Teutonic knights descended upon Pilėnai fortress. They outnumbered civilians huddled inside 2-to-1 and the lord of the fort, Duke Margiris, knew they faced certain death.

By this time, the Teutons had been attempting to crusade Lithuania for over fifty years. As the last pagan nation in all of Europe, Pope Benedict XII had ordered them to be converted or destroyed. Despite being massively outnumbered, however, the Lithuanians held their ground.

At Pilėnai, Duke Margiris knew they had no chance of defense. If they were to surrender, anyone who refused to convert to Catholicism would be tortured, killed, or enslaved. He and those trapped inside knew there would be no mercy for pagans.

He opened the fort to the Teutonic Order.

The moment they entered, civilians attacked with axes and farm tools. The gates were closed behind them and the fort was set ablaze, killing Lithuanian and Teutonic knight alike. It’s believed that over five thousand people died that day, making it one of the largest mass suicides ever committed.

This wasn’t the end of the crusade on the Balts, but the story of Pilėnai inspired the nation to hold to their pagan roots even when victory seemed impossible.

By 1410, the Baltic Crusades had been going on for nearly 150 years and the new pope, Gregory the XII, was determined to extinguish this pagan influence once and for all. Yet despite decades of attack, the Lithuanian territory refused to recede. When the Lithuanians managed to gain ground at Grunwald in Poland, Pope Gregory XII sent roughly twenty thousand Teutonic knights to march on them. As few as twelve thousand Lithuanians met them on the field. The battle would be one of the largest conflicts ever fought in medieval Europe… And Lithuania won.

But though Duke Vytautas prevailed on the battlefield with fewer than two-thousand fatalities, the future was bleak. They were the last pagan nation in Europe, making them the only target left for the Teutons. Like at Pilėnai, he knew they could not hold out forever; it would not be long before the Pope would call upon an even greater army. Pagans would be shown no mercy. They feared “blood to their horses bridles,” as had been described in other nations where the Order has invaded. Perhaps this is why, after winning Grunwald, Duke Vytautas converted to Christianity.

After his baptism, the sacred oak grove, known then as Romove (which translates to “sanctuary” and is rooted in the Baltic root rem- “to be at peace”) was destroyed. The grand oak that symbolized the tree of life was cut down and burned and the surrounding forest was leveled to dirt. For the first time since 500BCE, the flame upon the aukurus (fire alter) at Romove was extinguished. And the temple to the gods — the last of its kind in all of Europe — was demolished. These bricks were used to build a cathedral on the site and prevent any remaining pagans from worshiping there. Archaeologists have since excavated all that remains of the original temple: a set of stone steps, which now lay concealed in the church crypt.

But King Vytautas was perhaps not as compliant as he may have seemed. Upon the destruction of the old religion, he welcomed new ones. Temples, mosques, and synagogues were built in the capitol and people of all nations were invited to settle there, and proclaimed to be free people. King Vytautas protected the right for foreigners to live in accordance to their own beliefs and traditions, making Lithuania the first officially multiethnic, multireligious, and multicultural European state.

Yet, despite the destruction of Romove, this wasn’t the end of Lithuanian paganism. Romove — the sanctuary — may have been destroyed, but the old religion found a new sanctuary: the home of the peasant.

This is Part 1of a two-part series.